How to fuzz SOME/IP protocol - How did I get my name on the BMW Hall of Fame (Part 1)

In 2022, as part of the BMW Private Bug Bounty program, I reported several security vulnerabilities in applications using the SOME/IP protocol in the head units of BMW vehicle called MGU22. As a result, I was honored to be included in the BMW Recognition of Security Exports by the BMW automotive group. In this article, I’ll introduce you to the SOME/IP protocol and share how I fuzzed SOME/IP applications to find vulnerabilities.

What is SOME/IP Protocol?

Traditionally, the main communication method used in in-vehicle networks in the automotive industry has been signal-based CAN communication. CAN remains a widely used protocol within vehicles even today. However, in recent times, alongside CAN communication, there is a growing trend toward the use of Ethernet-based communication methods. One of the Ethernet-based in-vehicle protocols in the AUTOSAR standard is SOME/IP (Scalable Service-Oriented MiddlewarE over IP), which is a service-oriented protocol. BMW Group uses the vsomeip open-source implementation of the SOME/IP protocol.

As briefly mentioned in my previous post, Tesla also has vsomeip installed in its systems, but it is unclear whether Tesla uses the SOME/IP protocol in its vehicles.

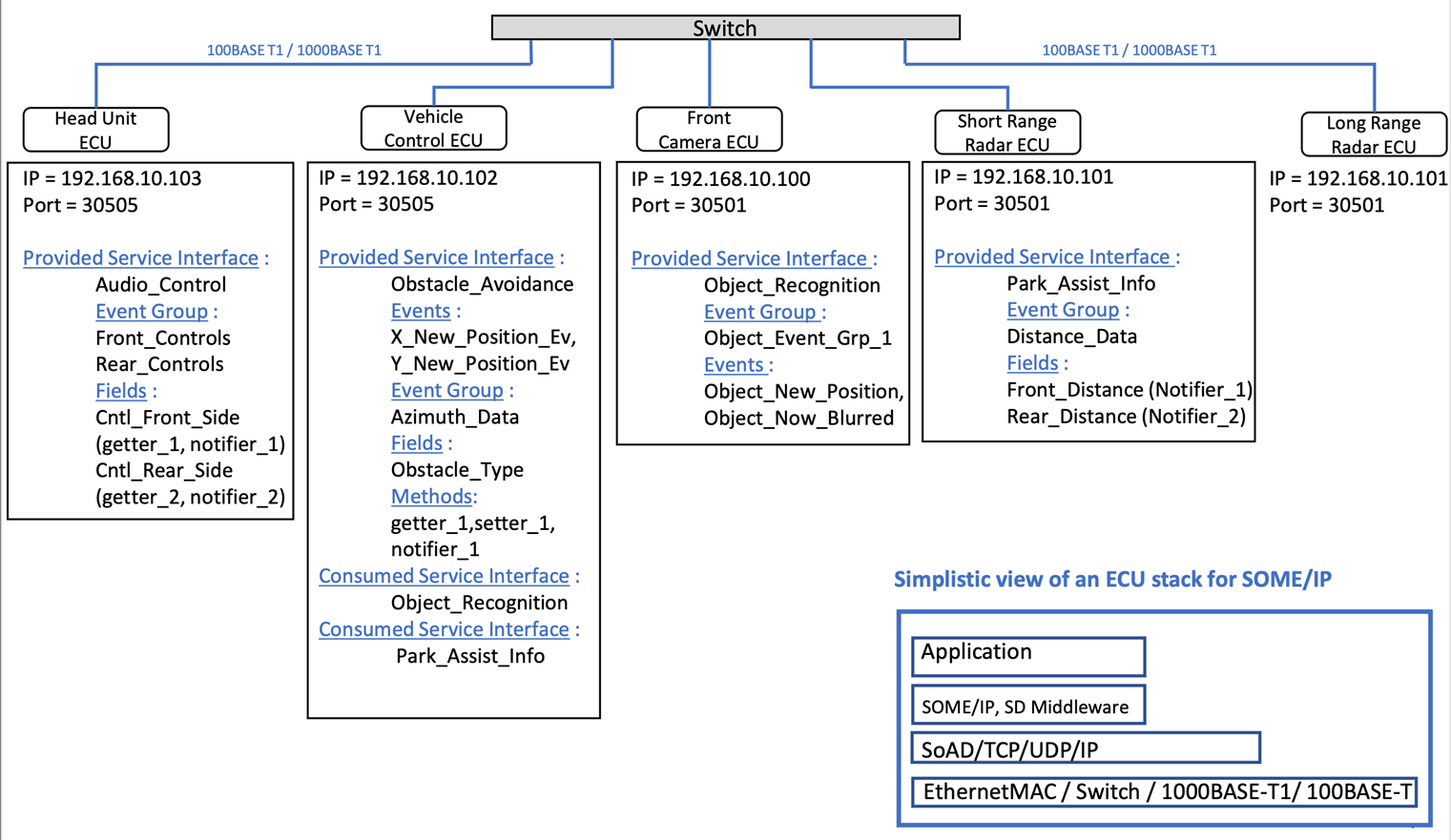

The figure below is a SOME/IP-based communication scheme for an in-vehicle network.

SOME/IP messages can use either TCP or UDP protocols. Additionally, service interfaces are distinguished by port number, so multiple instances of the same interface cannot be provided on the same port.

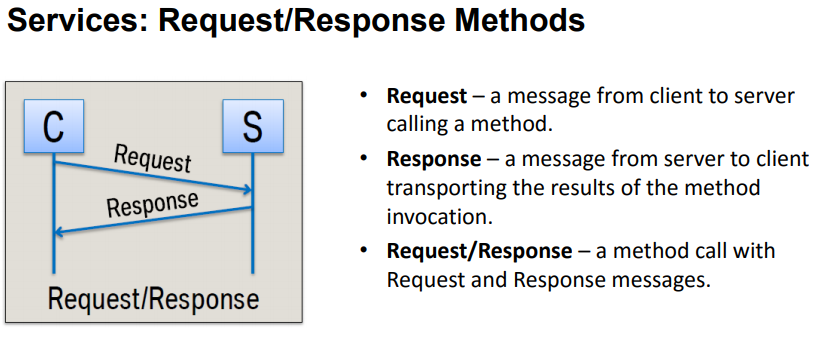

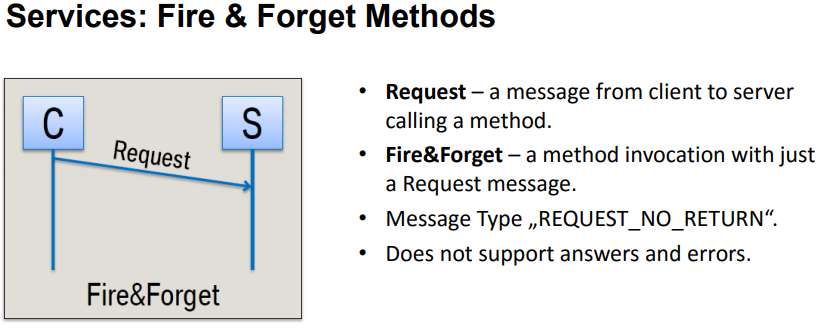

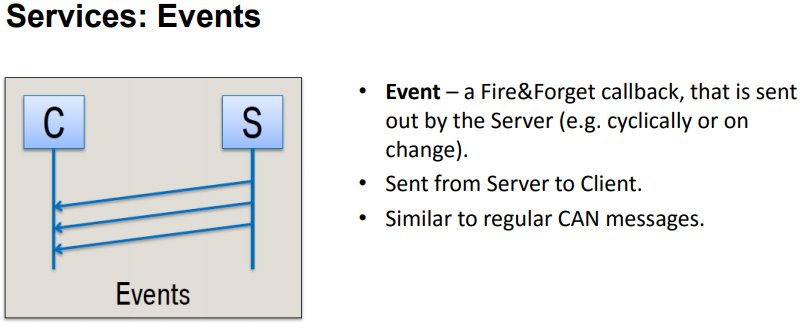

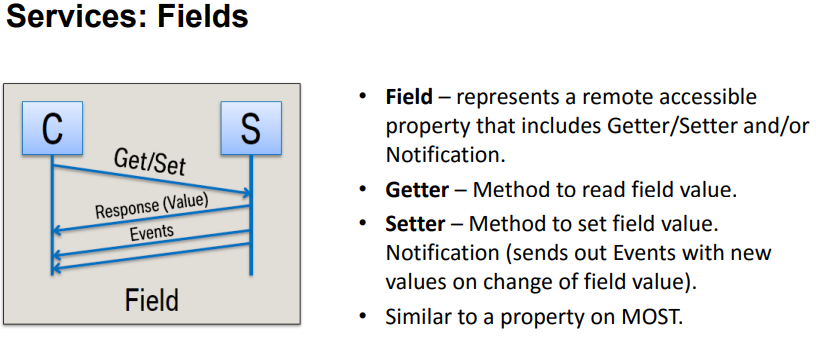

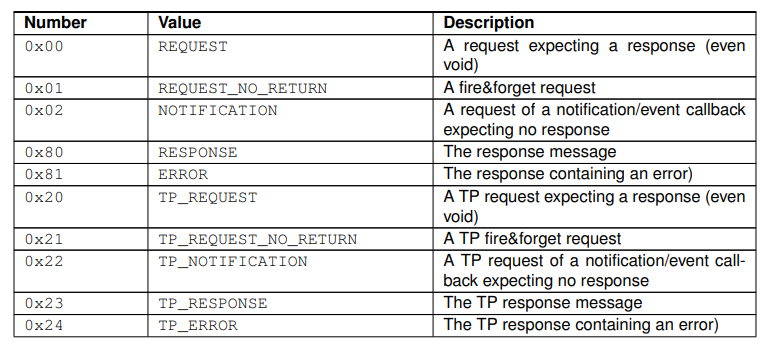

Messaging types are supported in four ways, as shown in the figure below.

The difference between Request/Response and Fire & Forget is whether there is a response message. Events is a messaging type where the server calls back when an event occurs.

For more information about subscribe, see the SOME/IP-SD (SOME/IP Service Discovery) protocol. We will explain it in more detail in part 2, but let’s first learn about the SOME/IP packet structure.

SOME/IP Packet Structure

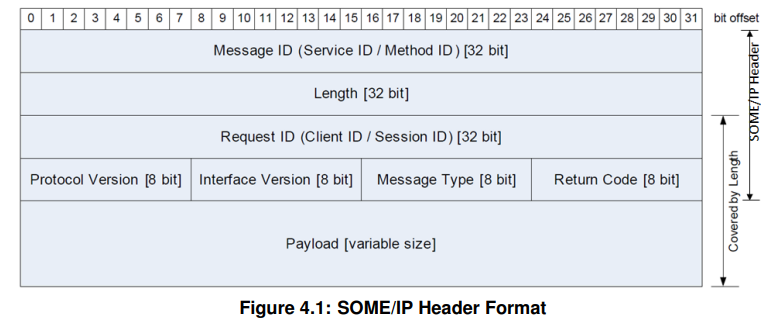

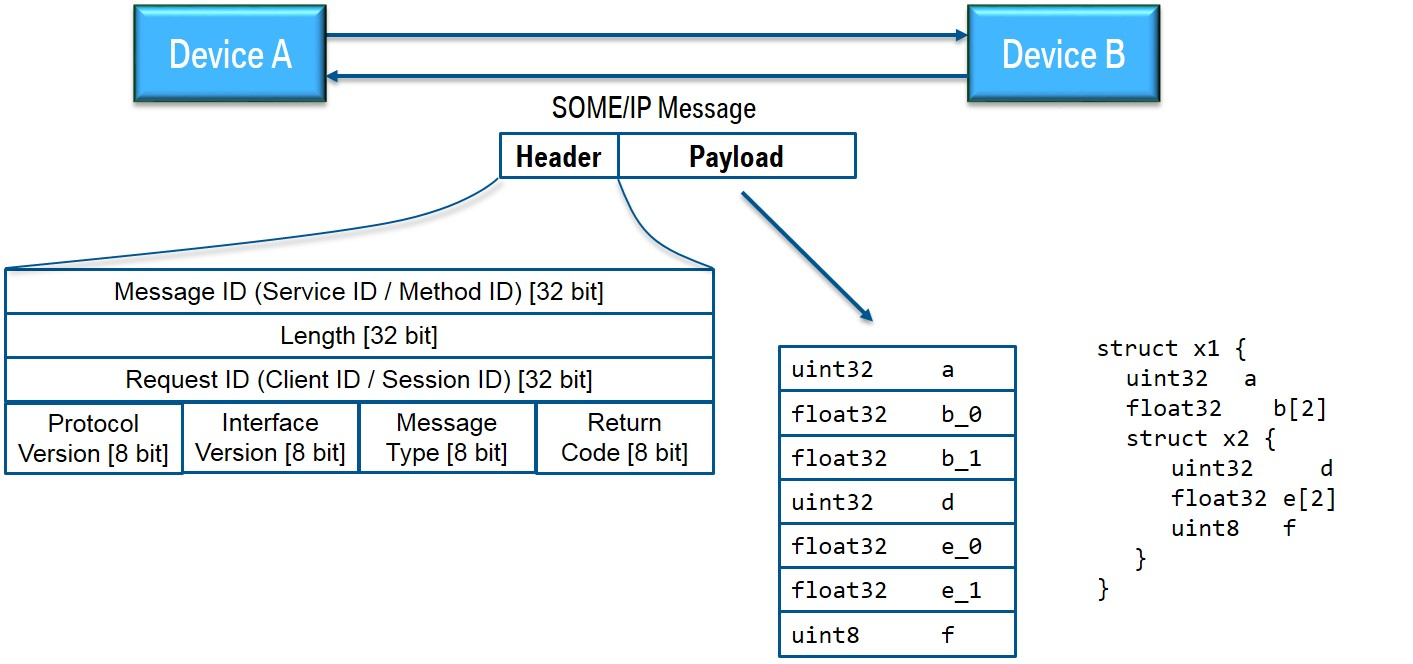

First, in order to send a normal SOME/IP message, you need to know the SOME/IP header structure. The figure below is the SOME/IP header format taken from the standard document.

Now, let’s take a look at each field of the SOME/IP header structure.

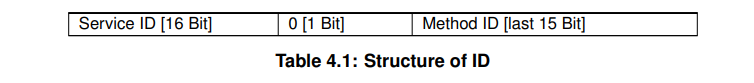

- Message ID

- Each service has a unique Service ID.

- Each service can have multiple methods, and each method has its own ID.

- Length

- The length from the Request ID to the end of the payload.

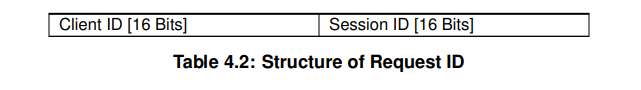

- Request ID

- The Client ID allows an ECU to differentiate calls from multiple clients to the same method.

- The Session ID allows to distinguish sequential messages or requests originating from the same sender from each other.

- Protocol Version

- It usually has a fixed value.

- Interface Version

- It usually has a fixed value.

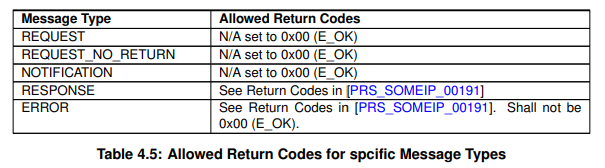

- Message Type

The Message Type field is different depending on the four messaging types mentioned above. For example, in the case of event messages, the message type is 0x2

notification, and the sender does not expect a response.

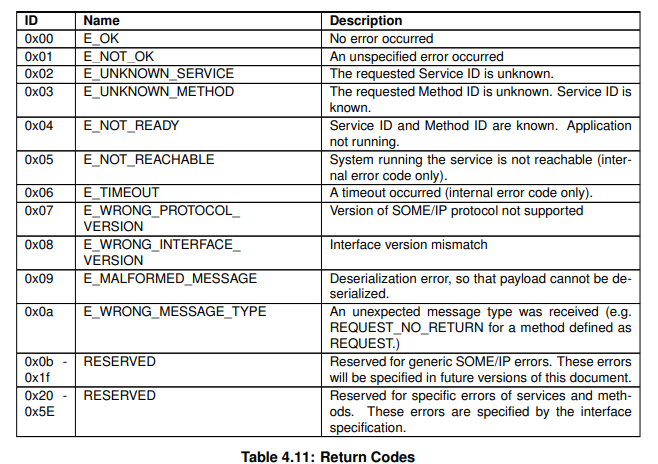

- Return Code A normal message generally has a return code of 0x00 (E_OK).

Let’s take an example. Most recent head units have Bluetooth functionality, which allows smartphones to connect to vehicles. In this case, let’s assume that there is a service called DeviceManager that manages devices connected to the vehicle. DeviceManager can have a variety of methods, such as connecting the vehicle to the passenger’s smartphone, checking the connection status, switching the connection to another device, and disconnecting the device. Additionally, it is possible that other controllers in the vehicle may want to receive device connection status in event format, as well as request/response format data requests to the head unit. In this way, a service can often be composed of a variety of methods and support a variety of messaging types.

Payload Structure

SOME/IP payloads are serialized before transmission, and the receiving side receives the data through the deserialization process. Therefore, random fuzzing, which sends random bytes to the payload, is unlikely to deliver the desired data to the application layer.

In order to perform structured fuzzing, you need to understand the variable types and serialization of the payload.

In the actual case of BMW’s MGU22, it uses SOME/IP related libraries of COVESA, and the implementation of each data type is in the code of the following link.

Here is a table showing some of the data types that make up the payload.

| Data Type | Byte Count |

|---|---|

| UInt8 | 1 |

| UInt16 | 2 |

| UInt32 | 4 |

| UInt64 | 8 |

| Bool | 1 |

| Enum | 1, 2 |

| Utf8 | Depends on the length of the string |

| Utf16 | Depends on the length of the string |

| Array | Depends on the length of the string |

| Map | Depends on the length of the string |

| Struct | 0 |

The following examples are code implemented in Python for each data type, and the return value is a hex string.

def _uint8(p):

return "{:02X}".format(p)

def _uint16(p):

return "{:04X}".format(p)

def _uint32(p):

return "{:08X}".format(p)

def _uint64(p):

return "{:016X}".format(p)

def _bool(p):

return "{:02X}".format(p)

def _enum(p, w=False):

if w:

return "{:04X}".format(p)

else:

return "{:02X}".format(p)

def _utf8(p):

data = "EFBBBF"

data += p.encode("utf-8").hex()

data += "00"

return "{:08X}".format(len(data)//2) + data

def _utf16(p):

data = "FEFF"

data += p.encode("utf-16-be").hex()

data += "0000"

return "{:08X}".format(len(data)//2) + data

def _array(p):

return "{:08X}".format(len(p)//2) + p

def _map(k, v):

data = k + v

return "{:08X}".format(len(data)//2) + data

For example, the UTF-16 character sequence “TEST” can be represented as follows.

print(_utf16("TEST"))

# the length of a string 0000000C

# actual string content "FEFF" + "0054004500530054" + "0000"

# return value 0000000CFEFF00540045005300540000

Also, the payload is composed of serialized data of multiple types Serialized data is simply a sequence of data types. If a data type requires a length, the length is prefixed to the data. For example, let’s consider the following data types serialized

Struct

{

UInt32,

Array

{

Struct

{

Utf8,

Utf8

},

},

Map

{

Enum,

Utf8

},

Bool

}

The following data types are serialized in the following order: Struct - UInt32 - Array - Struct - Utf8 - Utf8 - Map - Enum - Utf8 - Bool.

Struct is ignored in the serialization process. There are three main data types inside Struct: Array, Map, and Bool.

The Array contains Struct, Utf8, and Utf8 types. Here, Struct is also ignored, and in Python code, it becomes _array(_utf8("str1") + _utf8("str2")).

In the case of Map, it can also be represented as _map(_enum(data1), _utf8("str3")).

Therefore, the entire payload can be represented in code as follows.

payload = _uint32(data1)

payload += _array(_utf8("str1") + _utf8("str2"))

payload += _map(_enum(data2) + _utf8("str3"))

payload += _bool(data3)

In conclusion, the code to send a serialized SOME/IP message is as follows

import socket

import datetime

class SomeIP:

def __init__(self, service_id, method_id, client_id, session_id, protocol_version, interface_version, message_type, return_code):

self.service_id = service_id

self.method_id = method_id

self.client_id = client_id

self.session_id = session_id

self.protocol_version = protocol_version

self.interface_version = interface_version

self.message_type = message_type

self.return_code = return_code

def assemble_packet(self, payload):

self.header = "{:04X}".format(self.service_id)

self.header += "{:04X}".format(self.method_id)

self.header += "{:08X}".format(len(payload) + 8)

self.header += "{:04X}".format(self.client_id)

self.header += "{:04X}".format(self.session_id)

self.header += "{:02X}".format(self.protocol_version)

self.header += "{:02X}".format(self.interface_version)

self.header += "{:02X}".format(self.message_type)

self.header += "{:02X}".format(self.return_code)

self.packet = bytes.fromhex(self.header) + payload

def main():

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

sock.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

sock.connect(("160.48.199.99", 32504))

sock.settimeout(0.1)

def _uint8(p):

return "{:02X}".format(p)

def _uint16(p):

return "{:04X}".format(p)

def _uint32(p):

return "{:08X}".format(p)

def _uint64(p):

return "{:016X}".format(p)

def _bool(p):

return "{:02X}".format(p)

def _enum(p, w=False):

if w:

return "{:04X}".format(p)

else:

return "{:02X}".format(p)

def _utf8(p):

data = "EFBBBF"

data += p.encode("utf-8").hex()

data += "00"

return "{:08X}".format(len(data)//2) + data

def _utf16(p):

data = "FEFF"

data += p.encode("utf-16-be").hex()

data += "0000"

return "{:08X}".format(len(data)//2) + data

def _array(p):

return "{:08X}".format(len(p)//2) + p

def _map(k, v):

data = k + v

return "{:08X}".format(len(data)//2) + data

def someip_func(data1, str1, str2, data2, str3, data3) -> SomeIP:

someip = SomeIP(45246, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0)

payload = _uint32(data1)

payload = _array(_utf8(str1) + _utf8(str2))

payload += _map(_enum(data2), _utf8(str3))

payload += _bool(data3)

someip.assemble_packet(bytes.fromhex(payload))

return someip

def send_and_recv(someip):

try:

sock.send(someip.packet)

print(f"{datetime.datetime.now()}: {someip.packet.hex()}")

res = sock.recv(1024)

print(f"Recv: {res.hex()}")

except socket.timeout:

pass

send_and_recv(someip_func(1, "aaa", "bbb", 2, "ccc", 3))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

The code above is for sending a serialized message to the IP address 160.48.199.99 on port 32504. The service ID is 45246 and the method ID is 1. The messaging mode is request/response.

In this case, the session ID and client ID can be set to 0, and the protocol version is fixed to 1. The interface version usually has a value between 0 and 3.

The result of the above code is encoded as bytes and sent with the following values in hex.

b0be00010000003300000000010100000000001600000007efbbbf6161610000000007efbbbf626262000000000c0200000007efbbbf6363630003

We are now ready to send SOME/IP messages. However, we do not know the IP address and port to send the message to, the protocol type (TCP or UDP), the Service ID and Method ID, the message type (Request/Response or Event), or the data types that are serialized in the payload. If we fuzz by sending random data, the coverage will be very low. Therefore, we need to learn about SOME/IP-SD protocol to know each element.

SOME/IP-SD stands for SOME/IP Service Discovery Protocol. It is a message used to find service instances, detect whether service instances are running, and implement publish/subscribe processing.

In Part 2, we will learn about how the SOME/IP-SD works, connect a PC to the vehicle network, analyze SOME/IP-SD packet structure.